“Inauspicious Beginnings”1

My father was a very honest hypocrite.3 That is why he killed himself.4

He told me that I was born5 a white American man,6 and that no one on earth could ever have upon me a claim so strong as7 the one I made for myself8 and that it was up to me to make a last kick or two and die with some self-respect, because I’d done my best right up to the finish.9 By I he meant himself. 10

Then he explained to me what I was to do and what I was to say after he had gone.11 I never did get more than a general idea of the principle involved.12 You see I wasn’t paying any attention.13 I never do—especially when it don’t cost me anything.14 Our last conversation was extraordinarily stimulating.15 I hardly remember a word that was said.16

I am always thinking about Turgenev.17

***

Ever since I was a child, ever since I could read, I have longed to see the18 world through strange spectacles. I take no special credit for it. Perhaps my view is even a little grotesque.19 Everybody has a story concealed about their person.20 A small story, sir, cut straight out of the heart.21 I only want to read them.22

Shall I blame my father, my mother?23 My mother taught me how to pray, but24 my father taught me how to read the future.25 He taught me how to read26 in Pilgrim’s Progress, or some such book;27 seeing this, I quickly found my own legs, and rushed down the hill towards28 Turgenev and his great rivals.29 Into the streets of paper30 where life is free, in the third heaven of heavens, where the worlds are radiant, there31 I met with people who seemed really to desire to know what the Truth was.32 And in their search for truth they could scarcely find a resting-place for their foot; they looked round on the face of nature and recognized33 there was nowhere that they could flee, for this dense blackness was about to cover all the worlds.34

After that my father called me his mocking-bird;35 like a bird, that after flight on flight misses the shelter of its well-loved nest.36 I told him he was a fool, a plain downright fool, and he’d seen his last of me till he got us out of the mess he’d got us into:37 this business of living in a fairy story,38 of living in a world of only two poles, and someone finding both of them before we come along!39

***

My father was a great man.40 So-called great men are always terribly contradictory:41 they act like they know what they’re doing42—but they are not trained proof-readers, and they see the words in full rather than the individual letters, so that a wrong letter easily evades their notice.43 He committed many errors and gained no great victory.44

I have read his diary over again, though I haven’t got the skill to put it all down in words at full length.45 It nauseated me, but I could not stop reading, for the story was fascinatingly told.46 We have found that his life was larger than we knew.47 The more I do actually learn the more I discover how ignorant I am.48 He ate macaroni and drank white wine with mineral water.49 Macaroni makes you dream,50 and he dreamed of gigantic altruisms—the remaking of civilization,51 shells like cartwheels52 and sunsets like the Grand Canyon.53 A dream of his own born up there in the cold of his dead planet.54

And he yearned—how he yearned—to make use of it!55

With a real interest, which he gave humorous excess, he would celebrate some little ingenious thing that had fallen in his way, and I have heard him expatiate with childlike delight upon the merits of a new razor he had got: a sort of mower, which he could sweep recklessly over cheek and chin without the least danger of cutting himself. The last time I saw him he asked me if he had ever shown me that miraculous razor; and I doubt if he quite liked my saying I had seen one of the same kind.56

Why was I always such a stranger?57

***

Shortly before his death, waking from a period of torpor, he58 took me after breakfast to walk about the mountain.59

I did then put many questions to him verbally and took note of his notes of his answers.60 I asked him if he was always satisfied with himself.61 I asked him if he thought his son would obey him.62 Whether it was true that to pitch a ball required more skill than to catch one.63 Whether it was better to be an American even at the price of rebellion.64

We argued about art, religion, science, about the life of earth and matters beyond the grave—especially life beyond the grave.65 It rained the whole time that I was preaching; but66 that didn’t stop me from finishing my job on him. I left him in such a ridiculous fix that he was ashamed to complain.67 The air itself was all but visible, golden with the rain-washed sunlight, and all the trees and grass and bushes glittered, varnished with the rain-drops.68 We were like ionized particles, held within a framework, but each pulling away from the others,69 cast this way and that, not knowing whether to sympathize or hate;70 I was cast like a piece of the wreck, on a bleak, beaten, shelterless shore.71 All I could do was reel in the me-end of the line as fast as I could.72

***

Suppose the mountains were not thirsty enough to drink all of the raindrops, what would become of

the rest?73

Knowledge is atomic, existing in isolation; love is molecular, crystallizing in architecture. And yet even knowledge itself may, and very often does, become architectural; it is when it yields itself to the guidance of love.74 The raindrops that reach the land have many sorts of stories to tell before they again get back to the ocean.75

What it is like I cannot hear, for I am lost in its roar.76 I can only guess at the reasons for their decline and fall.77 I can only guess my own.78

I have heard it said that people are like waves, rising and riding and crumbling, and if a wave fell once on a shore long ago, then it left its mark on the beach and changed the shape of the world, but is not remembered.79

But the past is passed; why moralize upon it? Forget it.

See, yon bright sun has forgotten it all, and the blue sea, and the blue sky; these have turned over new leaves,80 and the earth turning like a wheel from west to east in its diurnal rotation81 is bringing new truths for the new age,82 new futures for people who might, in another day, have been consigned to the expendable, disposable list,83 but in this day and age, with the modern conveniences,84 will keep on turning for a long time, and only slowly lose its vigor and come to a stop85 when the wheel turns nearly the entire revolution.86

The wheel of my father87—the wheel that never stops its flight.88

***

TO THE CHILDREN

who will have

to live in the world

we are making 89

1. James Mott Hallowell, The Spirit of Lafayette (1918)

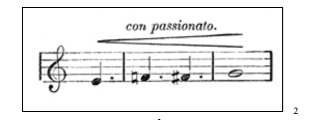

2. Anne Warner, A Woman’s Will (1904)

3. “The Country-House on the Rhine” from The Living Age, Vol. 102 (1869)

4. Francis Marion Crawford, Taquisara (1895)

5. Sir Andrew Sagittarius, The Perils of Astrology (1824)

6. Fannie Asa Charles, Pardner of Blossom Range (1906)

7. “Confessions of a Shy Man” from Chamber’s Journal (1850)

8. Thomas Hardy, Jude the Obscure: with a Map of Wessex (1907)

9. Ralph D. Paine, The Great America: An Epic Journey Through a Vibrant New Country (1908)

10. William Dodd, A Commentary on the Books of the Old and New Testaments, Vol. 3 (1770)

11. Maurice Leblanc, The Eight Strokes of the Clock (1922)

12. Charles L. Fontenay, “Z” from If: Worlds of Science Fiction (June 1956)

13. Agatha Christie, Murder on the Orient Express (1933)

14. James B. Connolly, Sonnie-Boy’s People (1913)

15. G. Jung, Collected Papers on Analytical Psychology (1920)

16. Alexandre Dumas, Ascanio (1904)

17. Edward Garnett, Turgenev: A Study (1917)

18. Fred M. White, Tregarthen’s Wife: A Cornish Story (1901)

19. “Personalities” from The Minnesota Magazine, Vol. 19 (1912)

20. The J. Paul Getty Museum Journal, Volume 13 (1985)

21. Tom Gallon, Jimmy Quixote: A Novel (1906)

22. Mrs. Alexander, The Admiral’s Ward, Vol. 3 (1883)

23. Samuel Richardson, The History of Sir Charles Grandison (1785)

24. The Offering of a Sunday-School Teacher to his Fellow Labourers (1820)

25. Walter McClintock, Old Indian Trails (1923)

26. John William Cook, Education History of Illinois (1912)

27. “Sunday Evening” from The Moral Picture Book

28. Hector Malot [Florence Crewe-Jones], Nobody’s Boy (Sans Famille) (1916)

29. Ivan Turgenev [Constance Garnett], “Introduction” from The Jew and Other Stories (1899)

30. “Street Cleaning Division” from Documents of the City of Boston, Vol. 2 (1837)

31. Thomas Lumisden Strange, The Legends of the Old Testament Traced to Their Apparent Primitive Sources (1874)

32. “Mission at Edeyenkoody, Tinnevelly” from The Colonial Church Chronicle and Missionary Journal, Vol. 13 (1860)

33. Stephen Watson Fullom, The Human Mind: A Discourse on its Acquirements and History (1858)

34. Sister Nivedita, The Web of Indian Life (1918)

35. Emma Dorothy Eliza Nevitte Southworth, Retribution: A Tale of Passion (1856)

36. Louis Untermeyer, “Sunday Night” from Challenge (1914)

37. Alice Brown, Old Crow (1922)

38. Elizabeth Rhodes Jackson, It’s Your Fairy Tale, You Know (1922)

39. Dallas Lore Sharp, The Magical Chance (1923)

40. George Bernard Shaw, The Millionairess (1936)

41. Maxim Gorky, Reminiscences of Leo Nicolayevitch Tolstoi (1920)

42. Vingie E. Roe, Nameless River (1923)

43. F. Horace Teall, Proof-Reading (1898)

44. Herbert H. Sargent, The Campaign of Marengo (1897)

45. Grant Allen, Wednesday the Tenth: A Tale of the South Pacific (1890)

46. “The Eyrie” from Weird Tales, Vol. 4 (1924)

47. Western Yearly Meeting of Friends, Minutes (1899)

48. Charles Kingsley, “The Reasonable Prayer” from The Works, Vol. 28 (1880)

49. John Burk, “Symphony No. 6, in B Minor, ‘Pathetic,’ Op. 74” from Philip Hale’s Boston Symphony Programme Notes (1935)

50. Gustave Flaubert, Bouvard and Pecuchet (1881)

51. Raymond Z. Gallun, “Eyes That Watch” from Comet (December 1940)

52. Gustave Flaubert, Bouvard and Pecuchet (1881)

53. Karle Wilson Baker, The Garden of the Plynck (1920)

54. Jack Douglas, “Dead World” from Amazing Stories (May 1961)

55. Ethel May Dell, “The Passer-by” from The Passer-by and Other Stories (1925)

56. William Dean Howells, Literary Friends and Acquaintances: Oliver Wendell Holmes (1900)

57. Selma Koehler, “The Question of Moral Responsibility in the Dramatic Works of Arthur Schnitzler” from The Journal of English and Germanic Philology, Vol. 22 (1923)

58. Ernest Ford, A Short History of English Music (1912)

59. Amelia Murray, Letters from the United States, Cuba and Canada (1857)

60. Sir William Napier, History of War in Peninsula and in the South of France (1940)

61. Henry David Thoreau, Walden (1854)

62. Emma Leslie, That Scholarship Boy (1900)

63. Abraham Cahan, Yekl (1896)

64. Carl Becker, The Eve of the Revolution: A Chronicle of the Breach with England, Vol. 2 (1918)

65. Ivan Turgenev [Isabel Hapgood], “The Rivau” from A Reckless Character and Other Stories (1878)

66. John Wesley, The Works of the Late Reverend John Wesley, A.M., Vol. 3 (1835)

67. James Brendan Connolly, Running Free: With Illustrations (1917)

68. Marjorie Kinnan Rawlings, The Yearling (1938)

69. Gilbert Seldes, Proclaim Liberty! (1942)

70. Arthur Ransome, A History of Story-telling: Studies in the Development of Narrative (1909)

71. Henry Kendall, “Frank Denz” from The Poems of Henry Kendall (1886)

72. Fritz Leiber, “A Hitch in Space” from Worlds of Tomorrow (August 1963)

73. “Object Lessons, on a Lake” from Texas School Journal, Vol. 4 (1886)

74. George Dana Boardman, The Ten Commandments (1889)

75. Harold W. Fairbanks, Conservation Reader (1920)

76. Alfred George Gardiner, Windfalls (1920)

77. Fritz Leiber, “Later Than You Think” from Galaxy Science Fiction (October 1950)

78. C. S. Lewis, Letters to Malcolm: Chiefly on Prayer (1964)

79. Michael Shaara, “Wainer” from Galaxy Science Fiction (April 1954)

80. Herman Melville, “Benito Cereno” from The Piazza Tales (1856)

81. John Tyndall, “On Force” from Fragments of Science (1879)

82. William A. Presland, “The English Conference to the American Convention” from New-Church Messenger, Vol. 87 (1904)

83. Traxel Stevens, “Continuing Education a Cure for ‘Disposable’ People” from The Texas Outlook (1916)

84. “Plumbing and Heating Equipment in California” from Sanitary and Heating Age, Vol. 83 (1915)

85. Herman Hesse, Siddhartha (1922)

86. James Slough Zerbe, Motors (1915)

87. Austin Spayne, “The Lost Jewels of King John” from Tales of Olde Boston (1902)

88. Lucius Annaeus Seneca [Frank Justus Miller], “Phaedra” from The Tragedies of Seneca (54/1907)

89. Gilbert Seldes, Proclaim Liberty! (1942)

DANIEL UNCAPHER is a PhD student at the University of Utah, with an MFA from Notre Dame. A queer and disabled Mississippian, his work has appeared in The Sun (2022 Pushcart Prize Special Mention), Tin House, Chicago Quarterly Review, and many others.