My father and I sat at our round kitchen table, the brown and yellow Tiffany-style lamp above enclosing us in its warm glow. I handed him an envelope; the paper stock was substantial. His fountain pen was already in his hand. My wedding was approaching, and my dad had offered to address all the envelopes for the invitations.

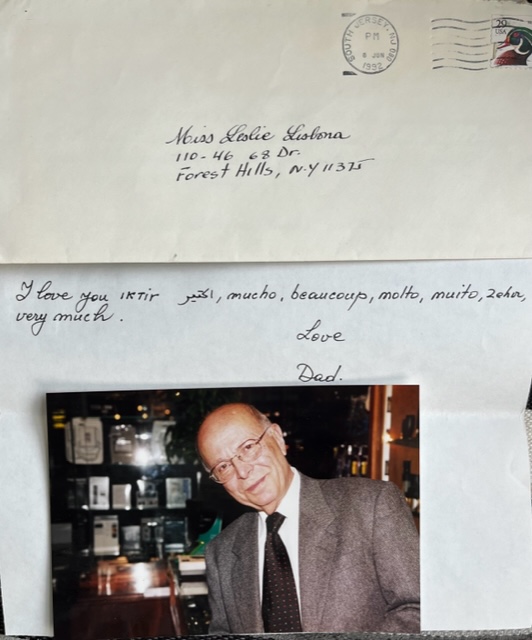

My father’s handwriting looked like loopy waves. It was hard at first sight to decipher one word from the next. But my eye was practiced. He had written to me when I was away at camp as a child. His letters were an addition to my mother’s, a P.S.

My mother had died only a year before this evening, suddenly and without warning. One day we were at the theatre, and the very next day she was gone.

Eight days before my mother died, my father was released from federal prison. They had eight days together. The three of us did. My siblings were married with their own households of children and dogs.

My father was a poor judge of character and let himself be aligned with two men who actually did do something wrong. In his gallantry, he tried to get them out of trouble, and instead he was implicated. He thought it would be sorted out in a trial; he had full confidence in the American justice system. He was terribly wrong. He lost his store and nearly bankrupted himself with legal fees.

When I was 25, he was sentenced to 10 years and did four and a half. He came home a different person. A little bit shattered, a shadow of who he used to be. He was afraid to touch money. He was cripplingly anxious about his monthly meetings with his parole officer. I drove him to the Brooklyn courthouse and waited for him in the car, biting my nails one by one. He told me what to do if he didn’t come out. He was afraid he might be sent back to prison. He had been tricked before.

I was his youngest child, much younger than my siblings, an afterthought. I knew from my mother that he hadn’t wanted another child. That money was tight, that they had to move to a larger apartment to make room for me. Now, at 31, I was all he had.

While my father was in prison, I agreed to live with my mother. It was just me and my mom in the house, waiting for his return. Waiting to start my life.

When my father came back, the three of us were together for a little over a week. After my mother died, I wasn’t sure my father would survive. I was afraid he would end his life; he had mentioned a pact he had with my mother. “I need you, Dad,” I would whisper. “Okay” is all he would say.

Now I was home with my father, the same house I’d grown up in, but everything felt different. My father was worried about me. And I was worried about him. It was a ricochet of “Are you okay?” between us.

He gave me his checkbook. We sat at the round kitchen table some nights while I paid his bills and he smoked. He would ask me what was for dinner. At first, neither of us knew how to make more than eggs, French toast, and hummus. During that year without my mother, I taught myself to make some of her dishes. My dad was my taster and adjuster. “More salt,” he would say, or, “Mom didn’t use turnips,” or, “Maybe we should add lemon?”

My father and I were learning how to communicate without her. Friday nights we went to the movies. Once I tried to pay for our tickets. “You are my baby,” he said and put the cash in my pocket. We watched Seinfeld and Friends on Thursdays. On Sundays we went to 108th Street to buy groceries like lebne and pita bread and produce from The Purple Pickle. One time we went to Costco near JFK, but we got lost and never went again.

I looked through the names and addresses on our wedding list. We started with his friends. The ones he had with my mother. The friends they had made when they were newly arrived from Lebanon, new immigrants learning a new language.

I said, “Litsia Angel.” He carefully wrote the name with a flourish. Then I read him the address and watched as he wrote it. The ink smudged a little when he got to the end. We both winced.

My dad handed it to me. I blew on it and placed it to the side.

“Should I do it over?” he asked.

“No, let’s just keep going.” I liked it the way it was.

While my father was in prison, he wrote me almost every day. On the days that I didn’t get a letter, my mind raced with scenarios of why. Most of the time it was because he couldn’t find a pencil. Sometimes he was transferred without warning to another prison, and his belongings, including his pencil, were confiscated. On the days that I received a letter, I would carry it around in my coat pocket or pressed in the book I was reading, like a talisman. I looked at it several times a day. Even though it was in pencil, it was still beautiful to see. I read and re-read his words. Each one so important. He ended each letter telling me how much he loved me, writing something in Arabic because there was no equivalent in English. “Lose,” he would write, his nickname for me, pronounced Lo-zay, meaning almond in Arabic, “I love you iktir,” so much. The Arabic suited his handwriting better. It looked like calligraphy.

Finally, towards the end of the day, it was time to write him back. I would smooth out his letter on my desk and answer all his questions, tell him about the book I was reading, how much I hated my job at the bank. I wrote things to him that I never would have said to his face. About my relationships with friends, with boyfriends, with my mother and siblings. I told him about our gentle dog, a mastiff called Cujo, and how the dog needed surgery on his leg. He loved that giant dog.

There were things I couldn’t tell him. My mother had made me swear not to. I couldn’t tell him that we were in our beds, my mother and I, during a home invasion. That three men had broken in, held us at gunpoint. That she and I had hugged each other, stared at each other, our faces nose to nose, thinking we were surely going to die. She made me promise. I wanted to tell him though. I thought it would help me sleep at night and stop being afraid, but she was right. It would only hurt him. I didn’t know that then.

I said another name, “Sam and Madeleine Ezrati,” and this envelope was already better than the last. He beamed at me. This made me smile, too. We did a few more and let the envelopes dry on the table.

He lit up a cigarette and breathed in deeply and then blew the smoke into the lamp over our heads. “Lose, let’s continue tomorrow night.” Before going to the living room to watch the news on his La-Z-Boy, he added a few things to our shopping list on the kitchen counter with his fountain pen and a flourish. I no longer had a dog to walk. It was just me and my dad. I turned off the kitchen light and went to bed.

LESLIE LISBONA’S work has appeared in Synchronized Chaos, Dorothy Parker’s Ashes, The Bluebird Word, The Jewish Literary Journal, and miniskirt magazine, and is forthcoming from the Smoky Blue Literary and Arts Magazine. She is the child of immigrants from Beirut, Lebanon, and grew up in Queens, NY.

The art published alongside this piece was provided by Leslie Lisbona and is a photo of her father’s calligraphy.