Here are our children in our red and blue canoes:

Sal, six, her eyes alive to the depth of water. Its slithering currents and fickle backeddies scare her. She rubs sunscreen on her arms and then the arms of her Blueberry Baby doll in an effort to protect and soothe herself and it is working, she has become brave;

Piper, nine, looking up and ahead, seeing clouds in the white water and white water in the clouds, quick with his paddle in the bow, drawing, prying, helping, digging into the physics of stroke after stroke;

Leo, eleven, grinning his expeditious grin at nothing in particular, telescoping his cheer to any passing fish or dragonfly, supported by a Crazy Creek chair on the floor of our more stable canoe. Transporting his weak, spastic body is the whole reason we are on the river.

And here are you and me, carrying our marriage along with our dry bags and barrels. Finding that it moves with less effort on the water. That it floats, even. At home, we sound like this: I don’t understand what I did wrong today or yesterday or the day before it hasn’t felt like you’re there for me I’m not criticizing you but I don’t feel good around you you’re being stubborn I’m trying to have fun do you think I like fighting I need you to talk to me I have a sinking feeling.

Drive our truck seven hours north from Portland, Maine to the head of the Restigouche River that defines the border of New Brunswick and Quebec, plop our gear and our orange cooler and our kids in our boats and push off from the sandy bank, the cuff of your pants rolled to mid-shin and always getting a little wet, miraculously we sound like this: Hon do you have the map yeah I put it in the clear tupperware I marked the first campsite it’s six miles downstream thanks it should be easy to find it has a picnic table for Leo to eat at the river’s so clear I didn’t realize there would be cliffs this is beautiful do you know that bird song?

We used to be backpackers, solo and together, accustomed to the uphill slog, the thrill of summits. We know how to thrive in a natural environment, exposed to the elements and with minimal supplies. The constraints of the river make sense to us, calm us.

More bewildering is the whirling pace of Little League and fiddle lessons, suburban neighborhood gatherings, the multiple daily coordinating texts and emails from Leo’s doctors and school support team. The stress of keeping up, keeping track, making sure everyone’s where they’re supposed to be on time and fed and Leo’s not going to poop in his pants on the way to our friends’ house because he still has accidents and you’re not going to say Damnit Leo, under your breath but loud enough to hear, when you get out to clean him up and Sal’s not going to announce it all to everyone when we get there.

When Leo was born with Cerebral Palsy, one of our principal losses was the dream of bringing our children with us on the trail. It took a few years before we realized a river was a long, watery tunnel into the wilderness.

At first we were afraid. Leo can’t swim, and if he fell in, would struggle to get his head above water. Piper and Sal were small. We would be out of cell range, far from a road, in places we’d never been before.

Still, expedition was critical for us, we practiced it like a religion, invested in it like a future. We planned our calendar around the ice melt in late spring and black fly season. We mooned our way through REI and LLBean for date night, spending money there instead of dinner out. In this way, the river stayed alive in us all year.

We started out with day trips, Father’s day excursions where we spied a turtle, careful to keep Leo and his granola bars from dropping overboard. Piper in a tantrum learned to cry in the confines of the canoe, among nets and pails and binoculars. Tenuously we strung the days together. I remember our first long weekend on the river, Piper gained expertise with knots on the bowline. Sal discovered watercolors. While we pitched the tent, you brought out a baby bottle filled with gin and tonic you’d packed at home when I wasn’t looking, complete with lime. And Leo’s knees were not so scraped. You had thought of knee pads.

Now you like to recite the names of the rivers we’ve paddled: The Presumpscot. The Restigouche. The St. Croix. The Androscoggin. The Saco. The Moose River Bow Trip (this one makes a loop, like the curve of a bow). This spring, we head up to the Bonaventure in Canada again.

Here are some scenes of accidental joy:

Leo

Leo paddles along with his one handed paddle. It attaches to his life preserver at the shoulder and extends like a robot arm at a 90 degree angle that dips into the water. His strokes are slight and mostly useless. The paddle cost us seven hundred dollars, we had to crowdsource from our extended family. But it is adjustable and should fit him for his whole life. And he’s out here, participating, propelling us just a little bit more forward.

Leo cinches his life preserver up ever tighter. It must make him feel safe, held. It’s morning and he sits on the sand, clips himself in and sets to work pulling the webbing as securely as possible, while the rest of us take trips from the campsite to the canoes, loading them up for the day.

Leo having success splitting kindling with an axe. No blood, and enough dry wood to start a fire. We let out our breath.

Piper

Piper and I float on our backs down the length of the island wrapped in our foam sleeping pads like burritos. The river is frigid and shallow, the rocks collide with our bony parts leaving bruises. We pop our heads up for the video you’re taking on the shore and smile like nobody’s business. We are gleeful together in the morning sun. We try to hold hands but get separated. Before we get carried past the tip of land, we stand and wade perpendicular to the flow, stumbling, screaming with goosebumps, and scamper back up along the shore to do it again.

We’re a team in our blue canoe. I sight a line through the big rapids ahead and call out directions, Right! Right! Left! and Piper is competent and we make it, we only scrape the sides of our canoe on the rocks but don’t get lodged across the river in a T and take on water, don’t tip to the side. The rush of survival is exhilarating.

Sal

Sal hunts for gummy bears, gummy worms, and gummy frogs that I hid in the trees all around our campsite. Some are spiked by a slot of sharp bark, some drape over a twig, some balance on a branch, some bask on a fallen leaf. Pockets bulging, she walks back to the firepit where we’re blowing on a meager fire, and offers up a taste of her loot.

Sal in a raincoat eating m&ms under a makeshift shelter of milkcrate and soggy sweatshirt at the bottom of the canoe. The drizzle is on and off and eventually she falls asleep under there. Always little Sal on the river with candy.

Sal masters the tent and puts it up herself. Sal takes her flashlight to pee in the night without waking anyone else. Sal wades into the river to fill the water filter bag. Sal flips the pancakes. Sal grows up before our eyes.

You and Me

We’ve given the kids “quiet time,” which means they entertain themselves for an hour after lunch with their journals and colored pencils. They stay in three spots, Sal under a pine tree, Leo in a grassy clearing, Piper on some rocks by the water. You and I take a sleeping bag down the trail that leads away from the campsite. It’s only an eighth of a mile or less and ends at a secluded outcrop in the sun. We haven’t had sex for quite a while and we really want each other. We’re quick about it, but then we curl together on the sleeping bag, snuggled, resting.

You

We navigate through some tame rapids but the water’s low and multiple boulders loom up through the surface, so paddling’s as much a game of push-off-the-rock as it is of steering. I look up to see you reaching forward in the canoe for Sal’s tiny paddle, and comically but worrisomely lapping your way over to shore. Turns out you snapped your old paddle at the neck while poling your way through that last stretch. It makes me proud to see you set to work fashioning a new one from a long slender branch and half the spare kayak paddle you threw in with our gear as an afterthought. Your rigged up paddle lasts the rest of the river.

I wish you could be like this all the time – peaceful, content. I wish you didn’t get so sucked into your job and travel to meetings and come home exhausted and grumpy about the sticky kitchen counters. I wish when you wished things were different, when you wished Piper would stop being bossy and Sal would always tell the truth and I would relax about holiday plans and Leo would be able to run, that you would go outside and visit the creek by our house and drink in the fluid twist of life that it is, and remember how it laughs impartially, and you could find some grace, or forgiveness even. But instead you pour yourself a drink of tequila with a giant block of ice and retreat to your office.

I wish you could feel proud of me too, at home, for the small accomplishments that make up my day that are not as ingenious or skilled as your paddle-craft, but that keep our family running nonetheless. In between seeing clients part time, I borrow books from the library that I know Piper will devour. I weed the strawberries. I arrange playdates. I give our chicken eggs to the bus driver. You say thank you and you couldn’t do it without me. But always you point out the weeds.

All of Us

Under a tarp in the relentless rain eating biscuits and gravy you made in the collapsible oven. The tarp is taut and keeps us dry if we stay close together. We play game after game of Five Crowns. We’ll have miles to make up in the afternoon and will be putting up our tents by moonlight.

The kids stand together on a bridge over a popular stretch of class 3 rapids many people play on for practice. We’re feeling confident and it’s a sunny day. We empty out our gear and try to run the rapids in an empty boat. We wave at the kids and plunge into the white water. We ride through one massive pillow of foam before we capsize. You catch my paddle and keep hold of your own. It’s all I can do to keep my toes up and flip onto my back. I know the position well and I’m not afraid, even though my back slams a rock and I’ve lost my contacts from my eyes. As I float beneath the bridge, I have the presence of mind to give the kids thumbs up and smile. Even from a distance I can tell they look worried. In the pool on the other side, I swim after the canoe with you and help drag it to shore.

Me

At the end of the trip, I never want to leave. I dread our truck on the roads leading home, you listening to the Red Sox through static, the kids bickering in the back. I don’t want to turn on my phone, don’t want to read emails about the start of school and how the middle school lockers will have combination locks that Leo can’t manage. I want to be able to go with the flow and trust that things will work out fine without my vigilance, but I haven’t found a way to let go at home the way I do on the river. It’s a tricky time of year as we climb onboard a busy schedule again, the kids struggle to adjust to new classrooms, I get overwhelmed and you hate my rising tension so we argue a lot even though it’s our anniversary then too. The sun is stunning at the end of summer in Maine and our truck glimmers in the pull off where we left it. On the drive, I say in my mind: Presumpscot.

Restigouche, St. Croix.

Androscoggin, Saco.

Moose River.

Bonaventure.

JESS PULVER is a therapist and mother of three living near Portland, Maine. She has recently returned to the writing life after majoring in creative writing over twenty years ago at Swarthmore College. Her non-fiction essays and poems have appeared in The Good Life Review, Waccamaw, Griffel, Scapegoat Review, Literary Mama, The Examined Life, and Kaleidoscope. In her free time, she tends a large garden, jumps in the ocean year-round, and tries to find other ways to slow down.

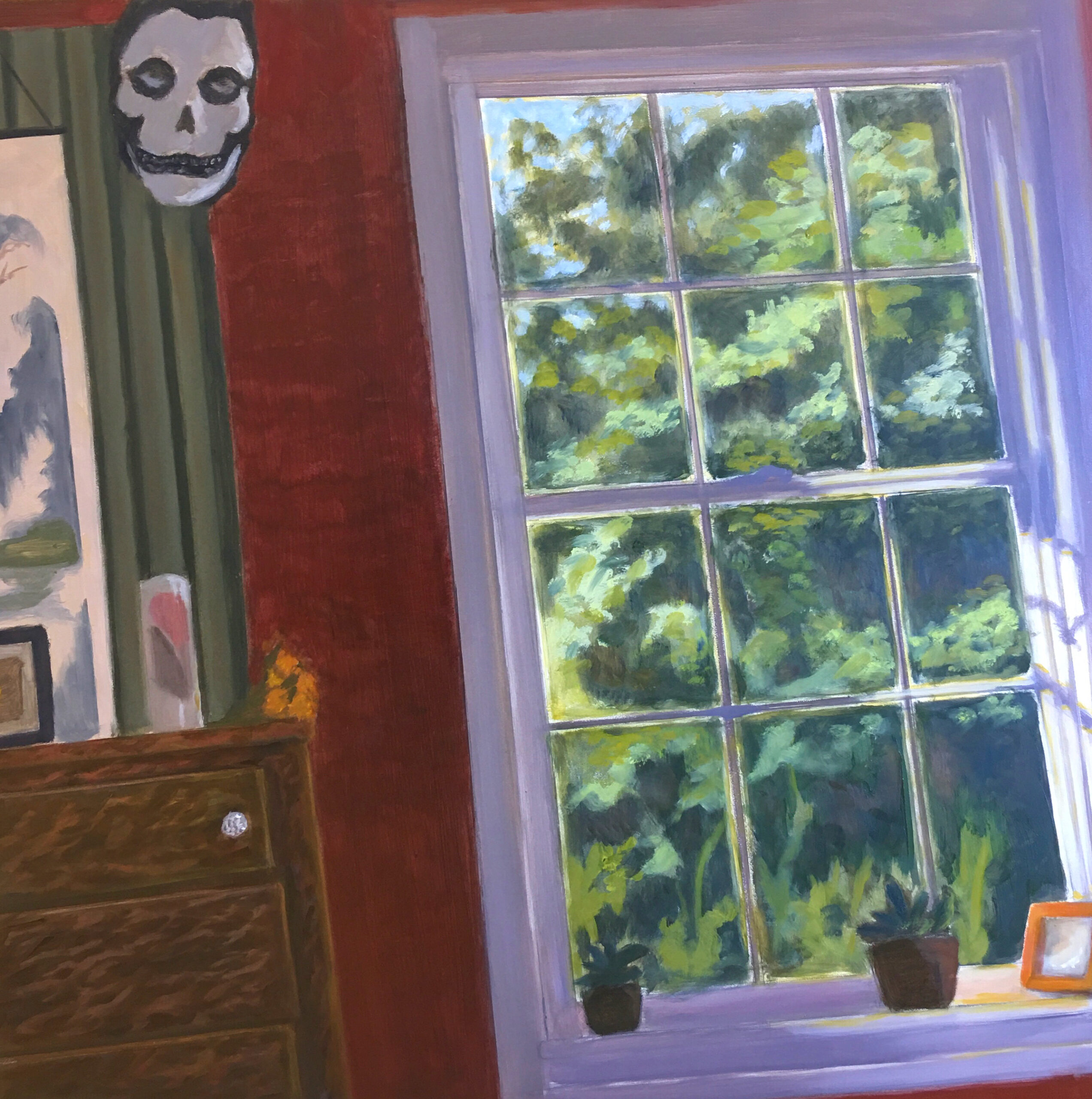

The art that appears alongside this piece is by AMY RENEE WEBB.