Tamara Al-Qaisi-Coleman (she/her) is a bi-racial Muslim writer, historian, poet, and artist. Her first book of poetry “The Raven, The Bayou, & The Willow ” is available through FlowerSong Press. She is a Brooklyn Poets Fellow (2020), a Rad(ical) Poetry Fellow (2020), and a poet for the Houston Grand Opera & MFAH’s event “The Art of Intimacy.” (2019) She was nominated for a Pushcart Prize and the Best of the Net anthology (2021). Her work can be found in (Art) WORDPEACE and Mixed Magazine, (Fiction) Crack the Spine Literary Magazine, (Poetry) Mizna, and others.

Conor Hultman lives in Oxford, Mississippi.

CH: In your collection, The Raven, The Bayou, And The Willow, there is a kind of dual-tension between traditions and mythology on the one side, and contemporary politics and cultural narratives on the other. How do you approach writing about the present, and how has looking to the past helped?

TC: I’ve always had a passion for history and the past, and in many ways, I feel like there’s a boulder on my chest pushing me down, pushing me to live in that bubble of trauma and survival. Countless events, large and small, had to take place for me or this book to exist. To me, there is no talking about the present, no writing about it, without the past, that goes for both the good and the bad. I’ve always been taken with the intertwining of history and memory, and how the past is shaped through both of those lenses. I write about the present/politics by writing about the history and the decisions that brought us to this point. I use poetry as a way to process big emotions or things I don’t understand. Looking at the past and analyzing situations or historical moments that I didn’t fully grasp at the time, is what drives me to write about politics and injustice.

CH: Many of the poems have the speaker addressing in the second person, creating an interrogative feeling. How important was perspective to the composition of these poems?

TC: Perspective is something that I consider constantly when I’m writing, I love playing with perspective and vantage points. How would the message be taken if the reader was the subject? Especially with my poems that are in the second-person perspective, it’s more like I’m writing a letter to an old friend. I can let out my frustrations as if I’m screaming into the void, an invisible person on the other side who has to weather the trauma masked in stories.

Different perspectives let me be as close or as far from the narrative as I want to be. The poems that I write in the third-person tend to be very close to home, that perspective allows me to take a step back. For me poetry is a confession, it’s a witness and the perspective it takes informs the subject just as much as the rhythm or the verse.

CH: “Ode to White Whales” is an example of how much mileage you get out of references. It expands the symbolic range on the sperm whale that Melville limited with his novel, and the poem takes this expansion as an opportunity for comment on colonialism, anthropomorphization, and natural history. How do you approach references in your poetry, literary, religious, and otherwise?

TC: I really love this question, because I am a reference nerd. I grew up being the “fun-fact” child, my parents blamed it on my ADHD and Anxiety. My larger understanding of the world and universe is that everything is connected, I’ve always been fascinated by connecting the dots of two points that seem too far apart to have a direct path. This poem, in particular, was an exercise in understanding myself and my people through an animal. I tend to get fixated on random things and at the time it was whales. I grew up with Melville and understood that Ahab’s fixation and obsession with Moby Dick was the undercurrent of a bigger commentary on race, fate, free will, etc. It felt so easy to use that reference and expand on the themes Melville was already commenting on. I approach references as the language in which I can be understood, I don’t need to code-switch or translate what I’m trying to say.

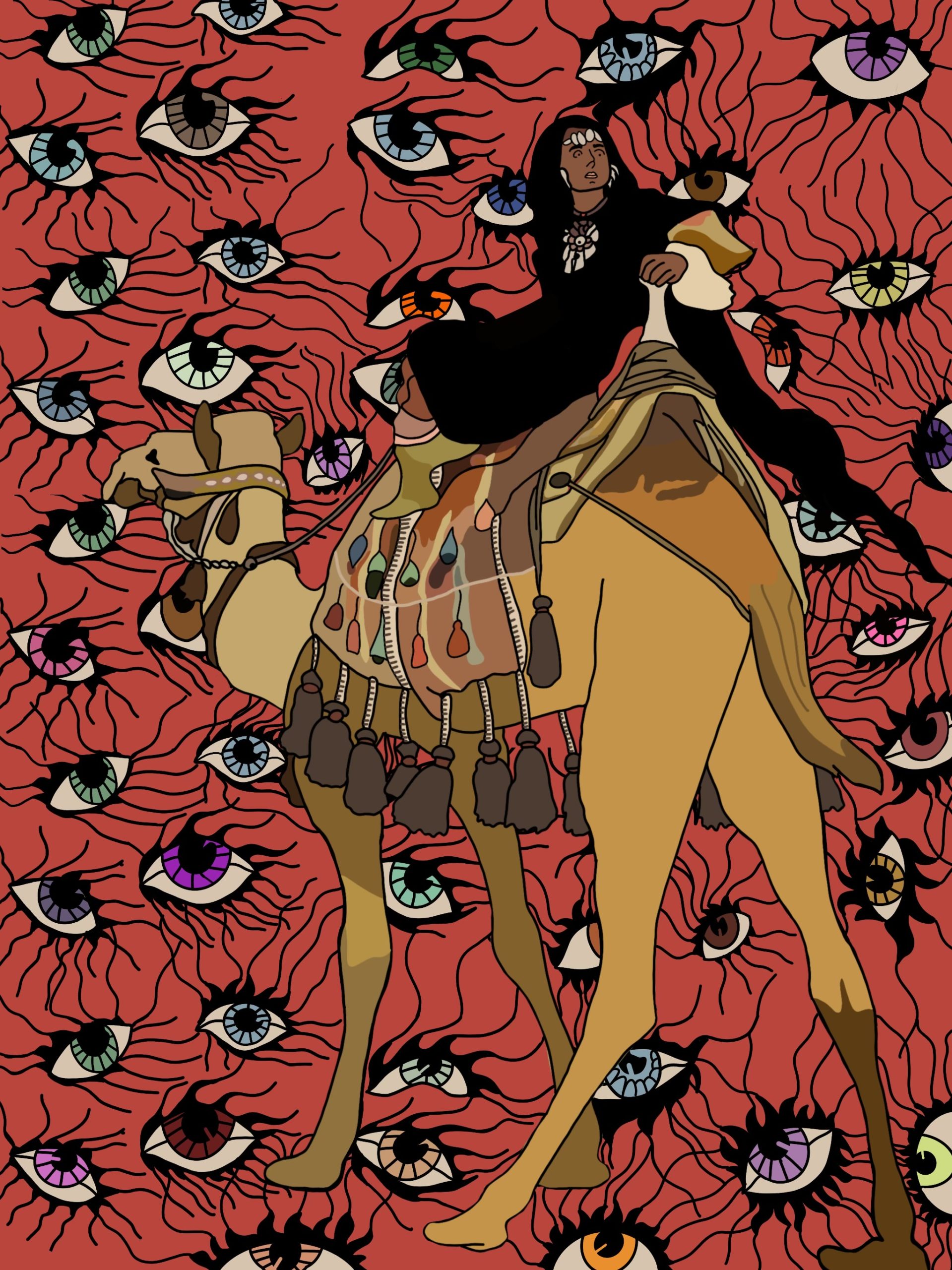

CH: I have to say something about the illustrations– not only are they gorgeous, but they inform the poetry as well. They really are inseparable from the words. What was the relationship in making this book between the poems and the drawings?

TC: The art in the book is inseparable from the poetry because I draw to work through my writer’s block. Drawing started as a way for me to work through my anxiety, and to understand the lens through which I saw the world. Often, when I’m stuck I will draw the poem until it feels right until I’ve moved through the block. In so many ways the poems would be incomplete without the art that goes with them, it would be like I half-published this collection if they weren’t there.

CH: Many of the poems have a natural but striking form. Your use of enjambment and space are especially engaging (like in a poem such as “Velasco”; the forward slashes dictate the rhythm in a way I found interesting). How do you find the form for your poems?

TC: Enjambment and space to me are part of the melody, the cadence, and the overall movement of the poems. My poems always follow their own flow, music was such a large part of my upbringing and who I am that it creeps its way into everything I do. It’s hard to describe how I find the ‘form’ of my poems. Usually, my poems start with a cadence or a melody I can’t get out of my head. The form comes from that melody, and I obsess over how that melody would play out visually on the page.

CH: As a fellow Houstonian, I am interested in the use of place in your book. Where did you find yourself writing about first?

TC: It’s always amazing to talk to a fellow Houstonian/Texan! I would say Sugar Land is the first place I found myself drawing from to write about. A lot of my poems deal with family and tension and childhood. Sugar Land is where I remember feeling at home for the first time, it’s also a place that holds a lot of history and trauma, both for me and Houston as a whole. I was always fascinated by the shift in population in Houston and its suburbs as I grew up. As I got older I spent the majority of my time in Houston proper—in the 610 loop. My perspective and understanding of Houston changed once again, with a new perspective and understanding of this amazing city, and so did my fascination and fixation on its varied neighborhoods.

CH: Which poem was the most difficult to write? Also, which poem was the easiest?

TC: Ooofff, there are many that could fit into these categories. The hardest poem to write would be “Mythos.” That poem is in the third person and very much drenched in mythology and story to mask the deep emotions I felt when writing it. It’s about loss, fractured memories, loneliness, chronic illness (masked as decomposing fungus), and anxiety. This poem is one of the first that I’ve written that really talks about the chronic pain I carry with me every day and it almost didn’t come together. I’m still unsure of how to write about/approach chronic illness and pain in my writing.

The easiest poem to write would be “Portal” it came from a workshop with Michelle Burk and Cait Weiss Orcutt. Our prompt was to take a memory and change it and make it fantastical. I always loved and relished the trips I would take to Galveston Beach with my friends or family. I had my first kiss in Galveston and the poem explores the memory of that first kiss but through the perspective of the history of the Gulf Coast. It was fun, which is what made it so easy.

CH: Do you believe poetry has the potential to affect political change?

TC: Absolutely. I say that for all forms of art. Music, visual art, performance art, poetry, fiction, comedy, anything that demands the attention of the audience.

Poetry is the expression of a lived experience, it is the manifestation of emotion and memory wrapped in the politics of its time. Even if a poem isn’t meant to be political it’s informed by the status quo of society at the moment it’s written, which in itself has the potential to change someone’s perspective of that same time period. To me, political change comes from understanding and revolution, poetry provides clarity and incites rebellion. For my people, poetry has been the way we tell stories, the way we gather as a community, and the way we manifest and create new realities.

CH: What are you working on now?

TC: Many things! I’m working on the second poetry book, currently untitled, centering more on pain and its different forms. How it can be killer and savior, how it is salvation, hope, and destruction all in one. I’m also working on a fiction project that focuses on ancient Mesopotamian Mythology.

Art by Tamara Al-Qaisi-Coleman and is featured in her collection The Raven, The Bayou, & The Willow