1.

Ants like blood.

People like blood.

Vampires like blood.

2.

Blood being blood is thick with strangeness.

The queasiness, the ick. The rush of it to the head.

Fainting is all about blood, all the wrong turns taken in the body’s transit system.

Yes the lust of it. Or for it, that is, which I don’t get.

Our blood possesses precious metal—gold in them thar veins.

Eerily, its composition mirrors the composition of pre-Cambrian seas.

As in: Once we bobbled in oceans of blood.

Maybe we have evolved, but the blood within us is ancient, older, wiser.

3.

I find this reassuring.

That something simple as blood carries within it so many layers.

I find many things reassuring.

I tend even after all the all of this of life toward a bit of optimism.

Being on the sanguine side.

4.

Another strange thing about blood is how funny it is—blood makes us laugh!

Once at Thanksgiving my aunt held a crystal gravy boat.

Said boat, slippery, slipped her grasp, shattered shards everywhere.

A glassy sliver slipped into her wrist.

Hence blood. Great gobs and gouts of the stuff.

My sister, too young to know better, laughed and laughed.

5.

Though maybe blood is more often tragedy.

As in Macbeth, the bloodiest king of all.

6.

Certainly it’s unexpected, the sometimes sudden gushiness of it. Sometimes we laugh just for that, the unexpectedness. Not from amusement but discomfort. The laughter researcher tells us that “…when we observe another person stumbling, some of our own neurons fire as if we were the person doing the flailing—these mirror neurons are duplicating the patterns of activity in the falling person’s brain…the observer’s brain is “tickled” by that neurological “ghost.””*

7.

Ghosts of blood, then.

Recently it seems to me this is what Rothko was painting, not the naked stuff but the blood passing through his shut eyelids, and all the light emanating beyond, between, and through.

White light. Red light. Yellow light, blue.

All filtered by a slender drape of eyelid flesh and, within, the even slanderer veil of blood.

8.

Now my aunt has bladder cancer.

Cancer, for all the allness it is, is usually fairly bloodless.

A vagrant illness, a hitchhiker worn out by the road, just looking for a place to rest.

9.

Though Capote might suggest otherwise. Cormac McCarthy would likely side with him. From the latter’s book of blood: “War was always here. Even before man was, war waited for him.”

Perhaps it’d be a bit more accurate to substitute truth for abstraction, blood for war—those pre-Cambrian seas.

As in: Blood was always here, was always waiting for us.

10.

But waiting for us to what?

Let it out, of course.

11.

The Aztecs freed the blood of the sacrificed as an act of reciprocity: the gods had shed blood to create the universe, so why not honor the generous act? Or the ancient Yoruba who sacrificed the companions of the recently dead so as to provide accompaniment in the afterlife—another kind gesture. The cult of Dionysus carried on in much the same as it were vein. And religious cults named for leopards, baboons, and alligators, all organized around blood sacrifice.

Of course the Eucharist. It’s almost too obvious.

12.

Other animals don’t blood sacrifice. Just us.

13.

One nice thing about blood is that it tends to confirm certain suspicions.

As in, Ouch, I think? Did that hurt?

Yes, says blood, it did.

14.

The elevator scene in The Shining is not scary. It’s not even funny.

Poor little Danny staring down the hall at all that gushing confusion. But blood come from where? A hose on the side of one of the two elevators? Does blood ride elevators? Whose blood is it? Where was it being kept? Who are those twins? Why are twins creepy? How long do carpets stain?

(Ed note: Confusion doesn’t create fear.)

15.

What’s actually scary is the moment you understand that something you’re afraid of, something you’ve long been afraid of, something you try not to think about, that you try not to ever give voice to, is very real and is upon you now.

As in your oncologist leaving a message: We need to talk.

16.

While what’s actually funny is a comment accompanying the elevator clip on YouTube:

@verlarn: That’s why I call my period The Shining.

(Ed note: Humor is about making surprising connections.)

(Ed note: While fear is about surprising disconnections.)

17.

Do vampires even like blood? Isn’t that like a baby saying, I like mother’s milk?

I don’t like mother’s milk. Who does?

Need is so very different from like, and don’t we generally come to resent the things we need?

Some, anyway? The visible ones?

18.

Maybe vampires rezent blood.

19.

Lucky us, that most of us so rarely see blood, so we can’t resent it, not really.

Instead we appreciate it. Even laugh at it.

Honor it. Mythologize it.

Certainly we fear it.

20.

Once, as a child, I tried to let it out.

Shitty knife, but some blood did usher.

21.

For years after I had a tendency to faint.

Luckily this was bloodless. But also bloodful: if you’ve fainted you know how it’s all about the sound of rushing blood so loud and loudening you can’t hear or see any more until

22.

Blood is a sign, sure, of the death that is to come.

23.

But just as often of life.

24.

Blood pudding. Blood sausage. Snake blood shots. Sweet blood pancakes. Black soup. Boat noodles. Bún bò Huế. Haggis. Czarnina. Blood pops. Boudin noir, a shade more elegant than coq au vin. Mole, supposedly. Blood bread, blood tongue, blood tofu. It’s fine. Everyone has pricked a finger and stuck it in their mouth and sucked. Salty. The Gadhimai festival in Nepal—it’s fine, the yaks are fine. Many cultures have sipped the blood of their living animals, just a touch, for sustenance. Maybe even a bit of flair—isn’t red more alluring than milk’s dull white? Though cannibals usually prefer meat to blood. Hannibal the Cannibal liked it all. Lover of life, that one. Zestful.

No one eats elephants, but we do love it when a plan comes together.

25.

Starfish have clear blood.

Imagine how different everything would be.

26.

I learn today that ants like blood after I swipe my left wrist across exposed pruning shears held in my right hand. After and for a very long time this moment keeps playing in my mind: ho hum I’m tugging branches and one branch comes loose and my left arm flies and the shears enter my skin, vein-clipping, and the blood comes and I watch it and feel cold not knowing what has been severed as in the street cars go past and bicyclists chatter and blood tumbles and I don’t know what it means or portends. Only fear. I don’t know that soon my wife will find and bandage me and take me to the ER and within five days the wound, the red little half-moon of it, half an inch from artery, will seal into scar, a lingering puffiness that very much belies all the blood that was.

27.

But that’s not the thing of it. After the ER is.

After the ER I get home feeling very tired and queasy, and I return outside to retrieve the offending shears, and I see, there, where the blood spilled, a rippling gathering of ants.

So many ants, standing at the blood drops’ edges.

One by one, the ants are picking it all up.

One by one, taking it back to the colony for the feast to come.

(*quoted lines from William F. Fry in Scientific American, “Ask the Brains,” October 2008.)

SEAN BERNARD is the author of the novel Studies in the Hereafter and the collection Desert sonorous, winner of the 2014 Juniper Prize. Recent work has appeared or is forthcoming in Santa Monica Review, The Iowa Review, and Copper Nickel. Since 2012, he has directed the BA Creative Writing Program at the University of La Verne.

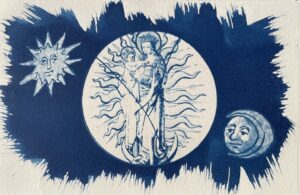

The art that appears alongside this piece is “the apocalyptic madonna” by GRETA KOSHENINA.